Education’s Vanishing Act

Once a top policy priority, now it’s barely on the radar. How can our schools get the attention and resources they need?

In May 2007, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart was near its late-night peak, fueled by savage mockery of the Bush administration’s Iraq War. One Tuesday evening, Stewart welcomed as his guest Bush’s Secretary of Education, Margaret Spellings. They had a substantive, civil conversation about the soft bigotry of low expectations and whether the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was working.

On a comedy show.

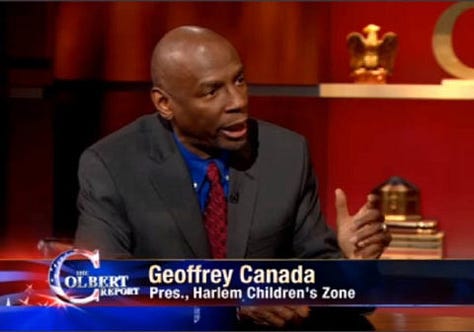

It was no anomaly. In the course of a few years, Stewart also booked DC schools chancellor and StudentsFirst founder Michelle Rhee. Historian Diane Ravitch appeared multiple times. The Colbert Report was even more engaged with education. Stephen Colbert interviewed Teach For America founder Wendy Kopp, New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein, KIPP co-founder Dave Levin, and Geoffrey Canada of the Harlem Children’s Zone - among others.1

Around the same time, Time magazine ran a famous/infamous cover story featuring Rhee. In 2010, NBC’s Meet the Press - then the highest-rated Sunday-morning political program with a few million viewers - devoted an entire special edition to education. Guests included Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, American Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten, and Rhee. They discussed the importance of accountability and teacher quality.

Education was a leading domestic policy issue. It was hot.2 American schools were improving. Optimism reigned.

Fast-forward to 2025. Public satisfaction with schools is the lowest ever recorded. In a recent Gallup survey, respondents were asked to name our nation’s most important problem. Three percent said education. Back in 2000, it was five times that many and education topped the list of concerns, beating out perennial hits like crime and taxes.

During last year’s presidential campaign, Donald Trump and Kamala Harris barely discussed education on the stump and were not asked about their plans in debates.3

Let’s face it: Education is an also-ran issue. Given that student outcomes are mired in a long depression, that’s worrisome.

How did we get here?

Education’s run as a top public concern was relatively brief, as Rick Hess and others have pointed out. There are several possible explanations for its decline:

No Child Left Behind passed. Congress took decisive, bipartisan action in 2001, approving the bill by margins of 90 to 10 percent in both houses.4 With the steam let out of the issue, folks quickly pivoted to hating on NCLB.

Other crises eclipsed education. The bursting of the dot-com bubble. September 11 and the War on Terror. The subprime mortgage crisis. The Great Recession. And so on.

Politics realigned. The Great Recession ignited populist energy on the right (Tea Party) and left (Occupy Wall Street). Matthew Yglesias did a great job of explaining how Republicans became much more conservative and Democrats became much more progressive, leaving education - which had been a centrist cause - ideologically homeless.

Fewer households have school-age kids. An aging population means there are more Americans whose priorities are senior housing and health care, not K-12 education.

Reformers overreached. During the Race to the Top era, we turned every dial to 11 simultaneously: higher standards, new assessments, explosive charter school growth, tougher teacher evaluations, etc. Backlash ensued.5

There’s more but you get the idea. Education got demoted.

The consequences of being an also-ran

Less public engagement with education has meant less momentum for improving our system. For example, where once there was pressure to improve learning for students from less privileged backgrounds, some states have recently created the illusion of progress by lowering cut scores on exams, enabling them to instantly declare more kids proficient.6 I doubt Meet the Press is going to air a special edition about that anytime soon.

I don’t mean to make a breathless claim that the sky is falling because education isn’t the #1 national priority. Nothing like that. The vast majority of our kids still attend public schools and their parents are generally satisfied with their experience. As has always been the case.

But things are changing. More evolution than revolution. Recent trends have reshaped the terrain in ways that deserve our attention:

Schools have fewer students. Two-thirds of traditional school districts lost enrollment between 2019 and 2023. Some are paying bounties to private firms to fill seats. Low birth rates guarantee this challenge will persist. Districts will be cutting costs and closing buildings.

Vouchers are for real. Thirty-three states now fund private school choice. Of those, 12 have no income cap on family participation. More states may follow suit now that federal law provides a tax credit for contributions to private school scholarship providers. Even blue states may feel compelled to opt-in.

Parents are increasingly wary. Many Republicans and Independents - who make up over 70 percent of the electorate - are dissatisfied with the amount of say they have in their own child’s education. Surveys show far lower levels of satisfaction among public school parents than their private school counterparts.

Headwinds against public schools are strengthening. At this rate, what will the playing field look like in another decade? I suspect we will see many more middle-class kids in private schools, subsidized by public dollars. Traditional districts will lose market share and increasingly rely on affluent, progressive enclaves and low-income communities as strongholds. Student outcomes will scuffle along, well below the historic highs of the early 2010s.

Are we ready to accept these outcomes as unavoidable? I’m not.

Three ideas:

#1. We need our leaders to lead

For nearly four decades, every U.S. president supported an education vision that included higher standards for students and the schools that served them. Reagan commissioned A Nation at Risk. Obama oversaw Race to the Top. Donald Trump (versions 1.0 and 2.0) and Joe Biden have done nothing of the sort.

The problem is not just federal. At the state and local level, I get the impression that some leaders take education for granted. They operate from an assumption that it remains a top priority. They ask for large funding increases each year and scream-sing “I BELIEVE THE CHILDREN ARE OUR FUTURE…” in a Whitney Houston karaoke voice if anyone balks.7

Other leaders attempt to make an affirmative argument for public education - but their case is strange. They appear to see our schools as noble but helpless; beleaguered, sainted, under-resourced, gamely trying to be everything for all kids. They maintain that we cannot expect positive academic results until all schools are “fully funded,” an ambiguous target that never seems to be met. Wash, rinse, repeat.8

I’m afraid this strategy is doomed. It sends the message that schools don’t work - and won’t work. Who is motivated by this sentiment? Only someone living in denial about the current populist era of distrust would bank on its success.9

Especially now, we need leaders who can champion public education to regular, boring people who follow the news and pay taxes and vote but don’t spend half their day posting about politics on social media. Where are my normies at?

For these folks - who are quite numerous - I submit that the best way to build support for education is to show confidently and credibly that it is good. Effective. It deserves our trust as an institution because it delivers. It converts dollars into happy outcomes for kids efficiently. It is accountable for doing its job. It fixes problems quickly when they arise. It is a service that understands our shared priorities and is focused on them.

Leaders need to offer better schools in exchange for more resources. That’s very different than “TEACH THEM WELL AND LET THEM LEAD THE WAY…!” ♫

#2. We need to give our leaders something to sell

Twenty years ago, mayors and governors could speak with a confident sense of possibility about education, pointing to spunky charter schools with gobsmacking achievement, record numbers of elite college graduates seeking to become teachers, and dysfunctional districts regaining their footing.

These days, what are we giving our elected leaders to work with? Most of them would readily admit they are opportunists. If there’s an angle that will help them score headlines and win elections, they’ll jump on it. Their silence is not just a lack of courage. It’s a lack of ammo.

That’s on us, collectively. As a sector, we need to put some wins on the board. Otherwise, education will remain irrelevant for the same reasons as the Chicago White Sox.

We have a vast array of non-profits and think tanks. They should be seeding a new generation of promising ideas. Where are the innovative solutions for chronic absenteeism? What are we doing to make teachers less miserable? What’s the 2020s equivalent of the charter school movement in the 90s? Right now, we don’t have one.10

Innovation isn’t everything. Excessive hype and premature scaling have humbled us in the past. But off-the-record, I suspect many elected officials would say they avoid education because they don’t see the play.

#3. Public schools should compete openly with private schools - especially in states embracing vouchers

A recent poll shows that 84 percent of independent voters say they would probably send their kids to a private school if public funds covered at least a portion of the cost. That’s a big deal.

But public schools have unique advantages they can leverage to rebuild family confidence. Transparency, for instance. Anyone can access detailed information on student performance or absenteeism for any public school - broken out by demographic group - with a few keystrokes. Most private schools cherry pick what they share and with whom.

Another example is proximity. Public schools are more likely to be neighborhood-based and walkable. When they are not, they provide transportation. For working parents, safe and timely buses are a godsend. Few private schools offer them.

What about fees? Tuition at private schools is just the beginning. They charge extra for all sorts of things, like sports participation, that public schools typically provide for free. Parents end up nickel-and-dimed. Or accessibility. One in six students has special education needs. Private schools are under no obligation to admit them or provide necessary supports.

I could go on about the quality of facilities, teacher salaries and longevity, or the breadth of course offerings.

Public schools - especially when they are executing at a high level - have a compelling value proposition. They should say so.

This has not been happening in recent years. When private schools bootstrapped solutions to reopen during COVID, many districts dithered for months. It cemented the notion that public schools are a safety net, not a high quality service. They are for unfortunate kids whose parents can’t send them anywhere else. I fear it will take decades to repair that damage - and it won’t happen without hard work.

Let’s play to win

Education once had a story to tell. It still does. Good schools work. They create transformative, lifelong opportunity. The operative word here is “good.” Mediocre, unfocused schools won’t get education back on the front burner.

I’ll finish by returning to Margaret Spellings, star of late-night 2007 television. Speaking just last week on an excellent webinar about current national achievement trends, she had a warning for those who dismiss our downward slide and see school performance data as a distraction.

“If we don’t have a problem, then we don’t need a solution. And if we don’t have a problem or a solution, then we don’t need money.”

She’s right. Jon Stewart, maybe bring her back on the show.

Who did I forget? I know there were more. Let me know in the comments and I can add.

Additional evidence of the issue’s hotness include Steven Brill’s scorching 2009 New Yorker expose on New York City’s “rubber rooms,” which memorably included a Queens principal going on the record saying “Randi Weingarten would protect a dead body in the classroom. That’s her job.” There was Davis Guggenheim’s 2010 documentary, Waiting for “Superman”, which was promoted by Oprah Winfrey on the same episode of her show where Mark Zuckerberg announced his $100 million investment in Newark schools. There was even Won’t Back Down, a 2012 feature film about a mother and a teacher teaming up to fight the school bureaucracy that somehow managed to make Maggie Gyllenhaal and Viola Davis forgettable on its way to earning less than $6 million at the box office. Still, we must marvel that a Hollywood exec heard a pitch for the concept and said “Leave my office and make this film immediately.”

There were good pieces on the near-total absence of education as a topic in the presidential race from Jessica Grose and Kevin Huffman.

Bernie Sanders, then a member of the House representing Vermont, voted against NCLB. Future Vice President Mike Pence, who was a House Republican from Indiana, also opposed it… likely for different reasons. If you looking for a good time, nothing beats reviewing old congressional roll calls. Who’s with me?

If you are new here, we’ve covered some elements of the backlash in previous newsletters, including this one on teacher evaluation.

Bonus points if your preferred rendition of “The Greatest Love of All” is by Randy Watson and Sexual Chocolate, via Coming to America. It’s a delight.

Even in some of the nation’s bluest strongholds, this is no longer working.

This recent profile of Milwaukee’s new superintendent, Brenda Cassellius, is a great example. She is sincere in her outreach, putting in long hours at community events. But do you get any indication that these efforts are going to address the nuts-and-bolts concerns families have? I do not.

I’m optimistic about some of the things I see in the works. They are nascent, but in 1-2 years, I think the picture will be different.

What a tantalizing footnote 10! I'm with you that there's a dearth of fresh ideas (other than maybe HSAs, but that's not really a new idea), and that we can do much better as a sector.

Education reform has lost steam, in part, because after decades of investment the returns have been modest and too often unsustained. Billions were poured into big bets that showed early promise but faded over time and often faced real community pushback in the process.

I saw this firsthand working in New York City during the Klein–Bloomberg years. Test scores and graduation rates rose, but not to the level many hoped would be transformational. The Gates Foundation’s Measures of Effective Teaching project produced important insights, but it failed to shift teacher practice or policy at scale. Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million investment in Newark promised a national model, yet the gains were limited and uneven once the spotlight moved on.

These high-profile efforts illustrate a recurring pattern: ambitious initiatives that briefly move the needle, then slide back because they weren’t built to last within the systems they aimed to transform. That history has made funders, policymakers, and the general public far more skittish about reinvesting in the current system and helps explain why more people are now embracing alternatives like school choice, vouchers, and ESAs.

Like you said, traditional public education can’t just be a safety net, it needs to be a high quality service going forward.