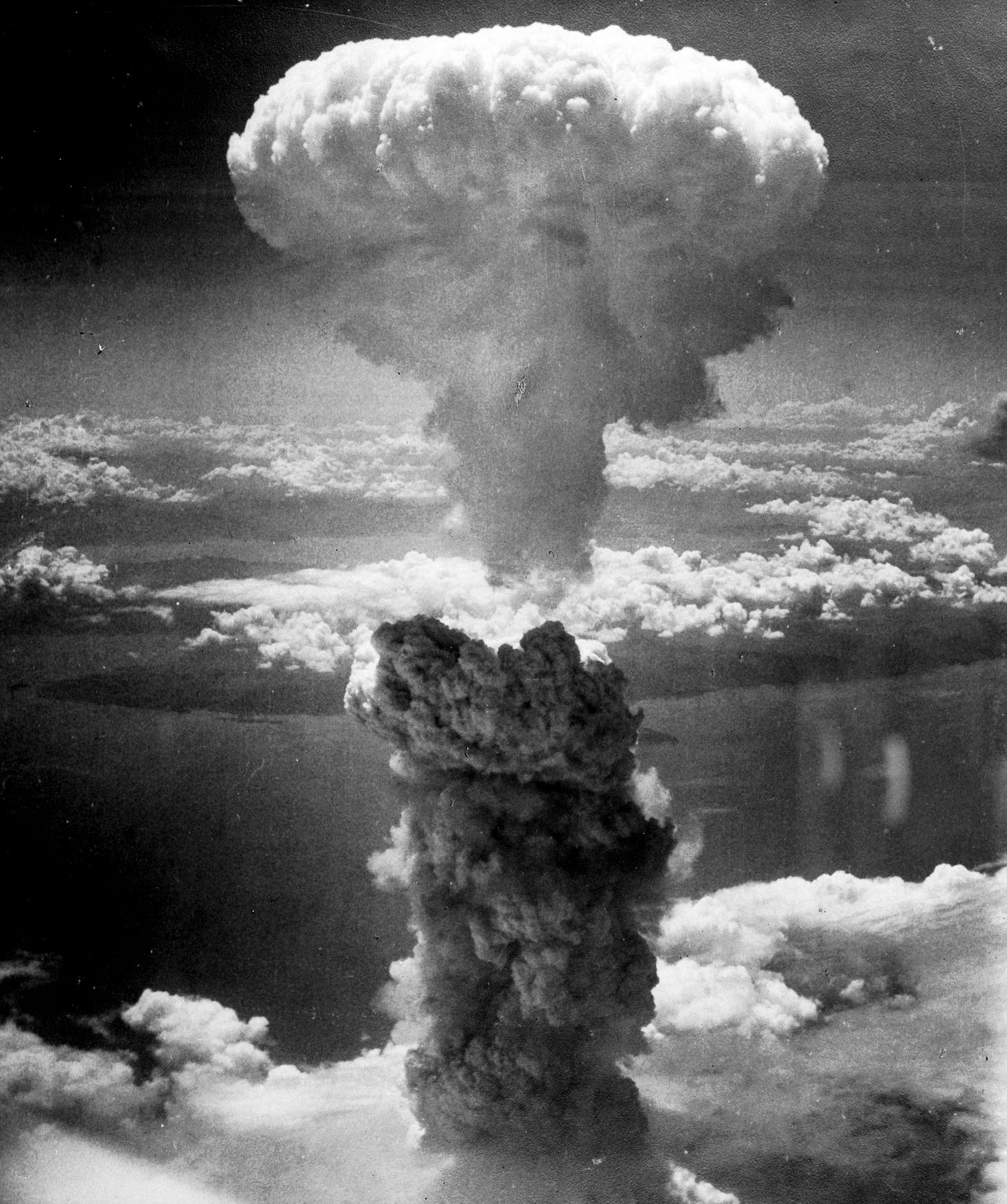

Enrollment Is a Time Bomb for Urban Districts

Tick... tick...

Here’s the first thing you should know about the mushroom cloud germinating over American schools: In 2000, Oakland had a total population of about 400,000; by 2023, it had increased to 436,000 - about nine percent.

Sounds like a growing, thriving city, no?

You might be surprised, then, to learn that Oakland’s schools are lately besieged by declining enrollment and massive budget shortfalls.

How does that math work? Did charter schools siphon students? Or perhaps parents were upset with COVID closures and opted for private schools or homeschooling?

Nope.

The cause of Oakland’s enrollment problem is mainly demographic change. In 2000, 25 percent of Oakland’s residents were under 18. In 2023, it was just 19 percent. Even as Oakland’s population grew by ~35,000, the number of under-18 residents dropped by more than 15,000 - which aligns almost perfectly to the district’s enrollment loss of 16,000.

Welcome to the new reality for our largest cities. Fewer kids. Half-empty school buildings. Eye-popping red ink.

There is a second thing you should know. Facing these headwinds, you would expect school systems to pull out the stops to attract more students.

But many of them are not doing that. Plenty of districts with empty seats make it needlessly difficult for families to enroll.

This is baffling. It is also counterproductive. If our cities don’t reverse both trends - failure to attract families with young children and to welcome them into public schools with open arms - the future for urban school districts is grim.

This enrollment reckoning is likely to become the biggest storyline in education for the next decade. Our districts are not ready.

The New Demography

Cities have fewer children than they did a generation ago. Eighty percent of metro areas are trending downward in terms of kids aged 0-14. In the three years immediately following the arrival of COVID, our three most populous regions - New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago - lost an astonishing 600,000 children. Rising costs for housing and child care, among other necessities, has made big cities unaffordable for many families. So they raise their children elsewhere.

Birth rates are way down. Let’s use Chicago as an illustration. In 2000, it recorded 50,885 births to city residents. In 2024, there were only 27,627. This decrease of 45 percent is often overlooked because Chicago’s overall population dropped only 8 percent in that same time span.1 U.S. families are getting smaller everywhere. The average number of children born per woman dropped more in 13 years between 2007 and 2020 than it did in 37 years from 1970 to 2007. Think about the magnitude of that data point for a moment.

There are more senior citizens. Out of 387 metro areas tracked by the census, 99.7 percent have more residents over age 65 than they did in 2020. A quarter century ago, there were 35 million senior citizens in the U.S. Today, it’s 60 million. Americans are living longer. Just as critically, Baby Boomers - who began turning 65 in 2011 - have flooded the zone. This is why some cities are not shrinking even as their schools do. They are swapping younger residents for older ones. But this means swapping priorities, too. Senior housing and health care are getting more attention from elected officials - and more tax dollars.

The primary issue is not that our cities are failing to persuade local families to choose public schools. Despite all the chatter on this front, the share of children in other school settings has increased only marginally over the past decade - peaking during the pandemic - and appears to be settling somewhere between 15 and 20 percent. The remaining ~80 percent of kids are still in traditional district schools.

But in a context where there are simply fewer children in the first place, districts needs to be extremely effective at registering those that live in their boundaries.

That’s not happening.

Some Districts Alienate the Families They Should Be Recruiting

At EdNavigator, helping families enroll their children in school is one of the main things we do. Pediatricians refer parents and caregivers who are likely to need additional assistance due to housing insecurity, language barriers, unique needs of their kids, etc.

Today, we’re publishing a report - From Gatekeepers to Greeters - detailing our experiences. As you can see below, some districts behave as if they want more students. Others make the enrollment process as cumbersome as possible.

For individual families, enrollment often goes sideways. In those cases, it looks like this:

Communication is messy. Enrollment steps aren’t delineated clearly at the start. New things are introduced - like a home visit to verify residency, requiring a parent to take a day off work - midway through. One staff member tells the family their landlord needs to sign and notarize a form. Another says the family’s state health insurance paperwork is sufficient. Information that’s shared in multiple places, such as on the district website and via forms given out at the registration office, often conflicts because it is not updated consistently in each location. When families get confused, they delay taking new steps until they are sure they are doing the right thing.

Processes are ridden with sludge. In-person registration may require online pre-registration, which can take hours. Websites aren’t optimized for mobile use even though many low-income families only access the internet through their phones. Districts require separate proof of occupancy and residency - sometimes through a visit to someplace like a town hall. Only then can they go to the district and enroll. Assistance is available only during certain days and hours. Does that sound fun?

Language supports are thin. Even when districts know a family does not speak English, they continue to send enrollment-related communication to them in English only. Interpreters are made available only when a family insists upon them and is willing to wait until one can be identified. Tech-enabled tools are getting better but they remain far from sufficient.

Delays are common. Students with more complex situations, such as an unstable address or a need for special education services, are frequently unable to enroll immediately. Perhaps there is just one staff member who handles issues with homelessness and that person is on medical leave, for instance. Even when state law dictates specific timelines, they are not consistently followed.

Consequences Are Mounting

Two things can be true at once. School systems can be victims of larger population shifts they are not well-positioned to influence. And they can drive further enrollment losses through unfriendly dysfunction.

Some districts don’t care. They figure they are still getting the same pool of local tax revenue to educate fewer students. Perhaps they are avoiding “hard to teach” kids whose needs will be more expensive.

This is a terrible mistake for three reasons:

#1. Districts are racking up mountains of legal liability. Some of the practices I described above are a class action lawsuit waiting to happen. One side effect of increased electronic communication is a lasting paper trail of family requests and office visits. The old “we never received that form” defense is not going to work so well. Moreover, the Trump administration would love nothing more than to shame deep blue states with civil rights investigations revealing their welcoming rhetoric to be hollow. And let me be honest with you: They will find plenty of evidence to support their cases. This will get expensive.

#2. Performance is suffering. Opportunities to identify and address student needs early are lost when kids cannot enroll. Instead, they stay home during the pre-k years and even for part of kindergarten. Their challenges are then more time consuming and costly to support for years to come. For rapidly diversifying districts and states, this can become a persistent drag on results. It shows up clearly in growing gaps between top and bottom performers. As accountability continues to loom on the horizon, district and state leaders ought to be paying attention.

#3. Public trust is eroding. Parents talk. When a district cannot do something as straightforward as enroll students, word gets around. In Massachusetts, where EdNavigator supports more families than anywhere else, there has been a record number of attempts to override property tax caps due to rising inflation. Public officials are discovering that voters will reject them. Taxpayers won’t spend more on schools with shrinking enrollment and substandard services. Especially not when districts have gone on a hiring binge for non-classroom positions.

Cities Will Compete For Families - and Students

It’s not that large school districts ignore demographics, exactly. Most of them have long term enrollment projections that are occasionally paraded before board members. The problem is that they receive little scrutiny even though they are comically optimistic - usually intended to justify expenses on personnel and construction that the superintendent favors.

If we had more independent, audited analyses, they would tell cities that they need a family recruitment strategy. Now. Either they attract more young families or they plan for a future with far fewer schools and employees. It’s one or the other. Though some large districts are attempting to set the world record for kicking the can down the road, the can will eventually shred. For those ready to face reality, Bellwether just put out a free toolkit full of good ideas.

Mayors need to provide far better leadership. Some of them are admitting only belatedly that they have a governance problem. City Councils should require contingency plans for low enrollment before appropriating district budgets - especially when they are presented with very expensive collective bargaining agreements full of new hiring promises.

Additionally, districts must pivot aggressively to a customer service orientation. How will they know if they are on the right track? We created a quick self-assessment to help them inventory their enrollment supports. Bottom line: The goodwill - and federal funding - from the pandemic are exhausted. If you pay any attention to education, you’ll read loads about the threat posed by President Trump’s desire to nationalize private school choice. Perhaps. But if I were a superintendent, I’d be far more worried about the trend of Americans losing faith in public institutions.

Oakland deserves credit in this regard. As we share in our report, the district sees its role as making it as simple as possible for families to enroll. Families can register online through a system optimized for their phones - without having to upload documents, like IEPs, that may be difficult to locate. Their goal is to get families in the door rather than to keep them out.

Given the harsh reality of today’s demographics, more districts will follow Oakland’s lead. They have no choice. Cities without an active strategy to increase enrollment are headed for a downward spiral.

The only question is whether it’s already too late. Tick… tick…

Shout out to Kids First Chicago, which did an excellent series on enrollment a few years ago, unpacking the various contributing factors. Relatively few cities have this level of detail. Boston has it via Will Austin’s very good newsletter. If there are others, feel free to flag them in the comments.

I was not quite screaming this from the rooftops last fall in Austin, but it sure felt like it. The writing was on the wall as early as last spring in Texas after the Republican primaries. Vouchers were going to pass. Meanwhile, enrollment in Austin has been on a 10 year decline with a significant number of barely filled, aging campuses. However, in our case the district only has ~60% of students in the area. 60%! The school board last fall was able to get a massive tax rate increase passed to partially cover a $100 million deficit which they blamed solely on inadequate state funding (a partial truth), instead of the massive bond packages to build new school buildings for campuses with almost no students and hiring that hasn’t reflected enrollment declines. And the number of stories I heard from parents who had a terrible experience with the district just trying to enroll their child was downright shameful - everything ranging from archaic computer systems to hostile school staff to no one answering the dedicated enrollment phone number. There has been zero effort to identify why almost half of students aren’t being enrolled in the district even with Texas’ voucher bill almost to Governor Abbott’s desk. And I haven’t even touched on the deep, decades-long disparities in student outcomes. It feels hopeless.

re: your footnote about other strong city examples... New Schools for New Orleans publishes a School Sustainability Analysis each year that is detailed and rigorous. (https://newschoolsforneworleans.org/our-impact/sustainable-schools/enrollment-landscape/ for Feb 2025 version). Over 5+ years, multiple charter operators responded to the enrollment pattern by voluntarily consolidating schools, merging, etc. This has meaningfully increased the "fill rate" of the average school. Fewer empty seats = more resources for instruction and student support. Also, somewhat expectedly, overall enrollment ticked up slightly in 2024-25.

Thanks for your post - informative and well-done, as always.