Will Massachusetts Remain the Top Education State?

The answer may depend on how it manages demographic changes that swept across its districts overnight

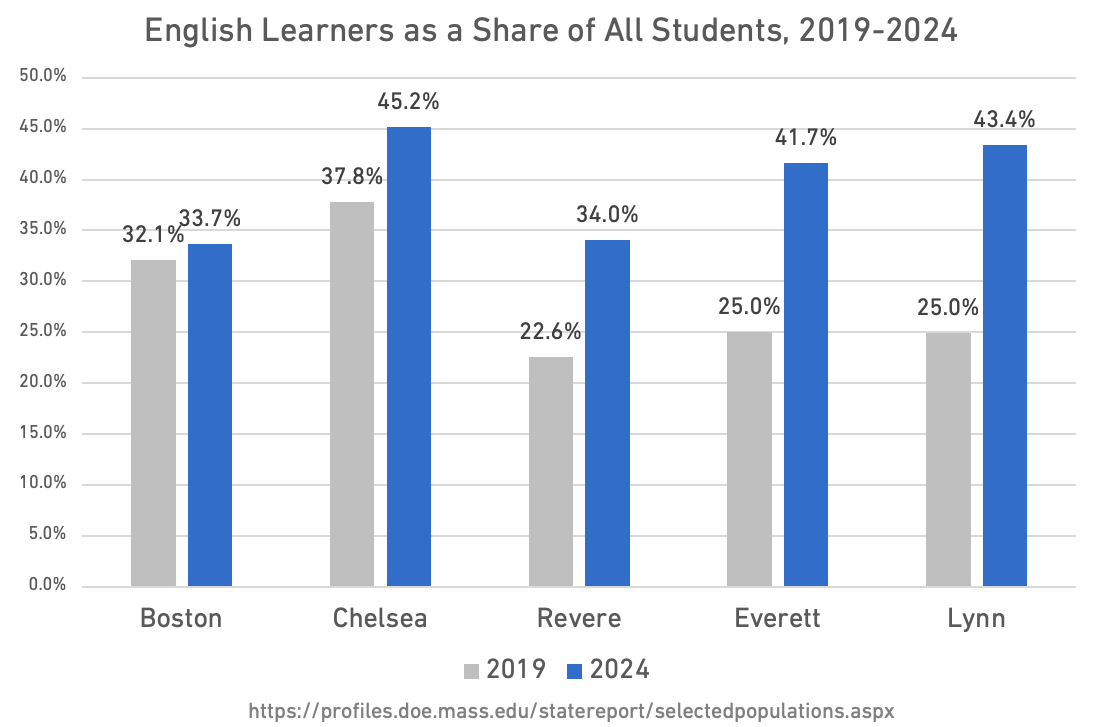

Everett, MA is a city of 50,000 located just north of Boston. Five years ago, on the eve of the pandemic, its school district enrolled ~7,100 students. Of those, about 1,780 - or 25 percent - were designated as English Learners (ELs).1

By the 2023-24 school year, the number of English Learners had grown to over 3,000, comprising 42 percent of total enrollment.

In raw numbers, Everett is serving 72 percent more English Learners than it did in 2019. That is a generation’s worth of demographic change packed into five years.

Declines in academic outcomes have followed. The percentage of Everett students scoring in the lowest achievement level (“Not Meeting Expectations”) for the annual Massachusetts English Language Arts (ELA) test jumped from 16 to 39 between 2019 and 2024. In math, it grew from 16 to 32 percent.

These test results have been influenced by the influx of English Learners, who are struggling far more than their EL peers from 2019. Back then, 33 percent of Everett’s EL students scored in the lowest level for ELA. In 2024, it was 63 percent.

Everett is not alone. Examples of COVID-era transformation abound in Boston. The neighboring communities of Chelsea, Revere, and Lynn also experienced sharp increases in EL enrollment. (The City of Boston itself barely nudged up, likely due to its sky-high housing costs.)

Similar to Everett, academic performance for EL students plummeted in these districts, with more scoring in the bottom achievement level. If you look to the left side of the graph, you’ll see the trend extends statewide.

Districts have pleaded for help.

This issue deserves more attention.2 Yes, we all know that public school enrollment declined during COVID. And yes, students lost massive academic ground during closures in 2020 and 2021 - ground that has never been fully regained. Those stories have been well told.

But some of the students who need the most support today weren’t even here in 2019. They attend schools that have been remade in half a decade. Plenty of districts have more students - not fewer - due to all the new arrivals.3

Districts are struggling to adapt

Here’s a snapshot of what it’s like when the number of English Learners explodes by 50 or 70 percent in a few years:

Staff are overwhelmed. Enrollment personnel are buried in registration forms that require verification of things like residency and vaccination with parents who may speak little or no English - and lack a permanent address. Individual teachers do their best with tools like Google Translate to communicate with families. Bilingual staff who can talk directly with families are asked to wear unlimited hats.

Critical services go undelivered. When districts cannot hire enough staff to fully serve EL students, they delay legally mandated special education evaluations or fail to translate important documents so parents can understand them. All sorts of things fall through the cracks.

Outcomes look bad. A combination of higher student need and missing supports leads to worsening academic results, as has been the case in a number of Massachusetts districts. Even the hardest-working educators will struggle to evolve on-the-fly to such a dynamic environment. When districts are slow to change the way they do business, it only gets worse.

Families bear the brunt

My day job gives me a front row seat for this part. EdNavigator accepts referrals from pediatricians when they see families during office appointments who need additional support working through educational challenges like enrollment and special education evaluations.

Since 2021, we’ve received over 2,500 referrals - most of them for Spanish-speaking families residing in Massachusetts. Our Navigators spend months helping them connect with schools and ensuring their kids get the resources they need. The retail-level experience is very difficult. That probably does not surprise you based on my description of what happens on the district side. Broadly speaking:

Families have no idea what to do. When they go to enroll, they find that every district has its own unique process. This form, that form. Everything must be done in a particular order. It’s rarely laid out in the language families speak. Messages sent asking for clarification routinely go unanswered. For newcomer families without a fixed address, the complexity is even greater. More idiosyncratic processes. In some districts, there is just one staff member who is familiar with the federal law that concerns homeless students, McKinney-Vento. If that person is on vacation or medical leave, nothing happens until they return.

Things don’t happen on-time. The delays I mentioned above are routine, especially for children who need to be evaluated for special education. But even when a student eventually receives an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), schools may lack providers to deliver services. A family might not be informed, for example, that their child is not getting the occupational therapy promised to them in their IEP for the past several months. Nor might the family be told they are entitled to compensatory services to make up for what was missed.

Many families give up. When parents attempt to register their younger kids for pre-K and don’t get follow-up from the local district, they often wait until the child is older and qualifies for kindergarten. In the meantime, the little one stays in daycare or at home, not learning English or receiving other supports that will prepare them for academic success. Data show this pretty plainly. In Everett, 45 percent of pre-K students are English Learners. For kindergarten, it jumps to 68 percent. Isn’t it in the interest of everyone - especially the district - to begin serving those EL students sooner? Perhaps this is contributing to the low EL test results we’re seeing?

All families benefit from a quality customer service experience. But for those facing language barriers, with fewer social networks and limited transportation options, smooth processes make all the difference in the world.

Districts are trying their best. But absent resources and a push for innovation, it is not going to be enough. Too many of them will function more like gatekeepers and less like greeters.4

We have two options here

On January 29, new national test results will be released.

Historically, Massachusetts has been near the top of the standings for each grade and subject.

Policy wonks are now whispering amongst themselves in muffled tones, wondering whether it has forfeited its edge through complacency. Long-serving, hard-charging Commissioner Jeff Riley departed last year. Recent academic signals haven’t been encouraging. A bill to mandate evidence-based literacy curricula died after pushback from unions and affluent districts, with Governor Maura Healey remaining silent.5 Voters eliminated the requirement for high school students to pass tests to receive a diploma.

I’m on-record as a prediction curmudgeon. We’ll have the data soon enough. But I can say with confidence that Massachusetts is grappling with more than pandemic learning loss. Its schools are feeling the shock of simultaneous, seismic events.

How Massachusetts responds will determine its outcomes for the next decade. There are basically two paths available.

The first is to ride out the demographic tide, hoping it’s a temporary shock followed by a return to pre-pandemic normalcy.

That’s not working. For most communities, there’s no sense chasing 2019. It won’t be back.

The dark side of this path is blaming problems on new arrival families, which is wrong on multiple levels. First, in many districts, achievement has declined across the board. It’s not just English Learners. Second, while some wish it weren’t so, all children in the United States are entitled to a public education, regardless of their immigration status. It’s the law. Districts that pretend otherwise will find themselves on the unpleasant side of legal liability.

The second path is to execute a strategy that gets the job done. Statewide. Cross-sector.

It’s not too late - but it’s getting close. To date, there’s been no emergency funding or additional assistance for Massachusetts districts grappling with demographic changes. Consequently, families are traversing red tape barriers on their own - with limited success.6

The task of identifying solutions will fall to the new K-12 Commissioner, who has not yet been hired and probably will not be on-the-job before summer.

The playbook, from the governor’s office down to the classroom, should look something like:

Insist on coordination of operations, funding, and data across agencies overseeing housing, health care, education, and transportation - for a start. Consider simplifying or standardizing the steps of enrollment statewide so everyone can understand them and help families traverse.

Find resources for districts. If we ask districts to serve lots of new EL students with zero new money, we can’t be surprised when it doesn’t work.

Provide front-end support for families so they can access mandated services rather than relying on after-the-fact complaint and resolution channels that will be unused and ineffective. EdNavigator is one example but we’re far from the only option.

Set some goals. What outcomes should be evident for districts, schools, and students? How long should it take for new students to get enrolled? To become proficient in English? To demonstrate proficiency in math and ELA on state tests?

Rediscover district accountability. Advocacy groups should not be forced to sue school districts to ensure legal compliance. Especially if the state delivers overdue resources and help.

Twenty-five years ago, when Massachusetts was completing its rise in the academic rankings, it had the same share of English Learners as Montana and Minnesota. Today, it has a higher percentage than Arizona.

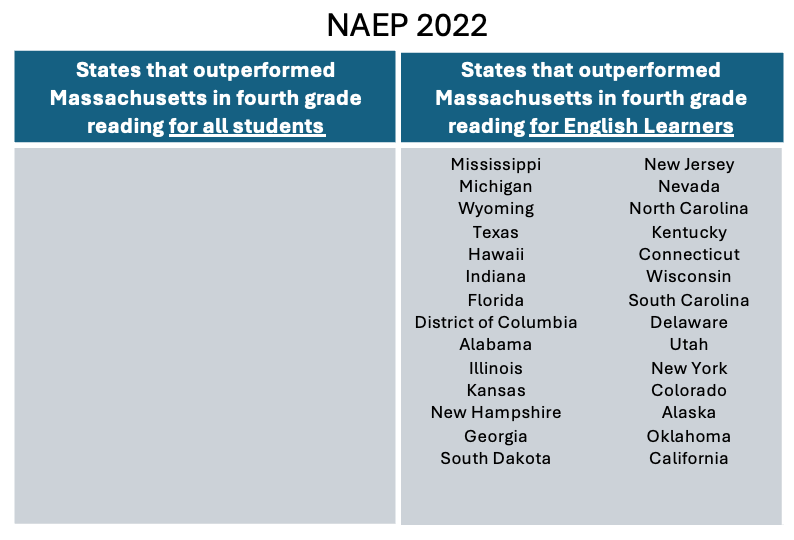

The only way for diversifying states like Massachusetts to remain top performers is to lead the way with innovative models for supporting English Learners. Otherwise, the numbers just won’t work. Consider the chart below:

It’s the right thing to do for kids and the best strategy to deliver results. The question is whether highly-ranked states - and you could add Utah, Connecticut, and New Jersey to the list, among others - will respond before they are surpassed. Your guess is as good as mine.

Detailed data available from MA available here. Throughout this piece, I will use the term “English Learner,” as does Massachusetts, though other states vary pretty widely in their preferences.

Will Austin is an exception - he’s written about this issue in his weekly Boston newsletter, which you should definitely subscribe to.

Boston is an example - it just announced its first enrollment increase in a decade. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/01/14/metro/boston-school-enrollment-increase/

Look for a new report from EdNavigator on this issue in the spring, including national examples of districts taking promising steps to accommodate new arrivals. There are positive outliers.

While Healey did not get behind the bill to mandate literacy curricula, Riley did so publicly. It remains to be seen whether the ongoing education depression leads governors to play a more assertive role with schools.

EdNavigator is doing high-touch support only for families who get their pediatric care at specific practices in the Boston area. Financial support comes from philanthropy and the health care organizations themselves.

This article misses the mark. The problem is so much larger and more profound than the delayed bureaucratic mess in schools and school districts

1. ELL students don't receive IEP's unless they have an identified learning disability. Not knowing how to speak, read, or write in English is not an LD.

2. ELL students are required to take state standardized tests one year after arriving in the US, well before they have reached mastery level in literacy. Typically, it takes 3-5 years to reach academic language proficiency, yet DESE includes their scores with those of native English speakers

2. Where's the data about the change in SES status of a significant portion of newly arriving students? The increase in students from low-income families should have been included in our article. What percent of students are designated as SLIFE? These students have limited schooling and first-language literacy and require a more intensive academic experience

3. You do not mention the impact of the teacher shortage. Educators are leaving the profession in significant numbers. In addition, the number of applicants to graduate schools of education has dropped by 30% nationwide in the last 10 years. The pipeline is drying up and the shortage will soon reach crisis levels.

These problems didn't begin in 2019. As any student facing educators can tell you, the problems began to surface at least 12/13 years ago. They can also tell you that the top down approach has failed - miserably. The Commioner of Education has little to no impact on what goes on in a classroom. or a school. They come and go and no one at the local level even notices or cares. The state and local focus needs to be on getting sufficient resources to the people who are working with children - more personnel in classrooms, more mental health supports (social workers, guidance counselors), reasonable class sizes, updated curriculum materials.

I hope you will continue to look at this problem, but in a deeper way. The PISA and MCAS scores provide little insight into the increasing problems in public education.

Jane Frantz