Cheese Buses Will Save Our Schools

Why field trips matter more than ever

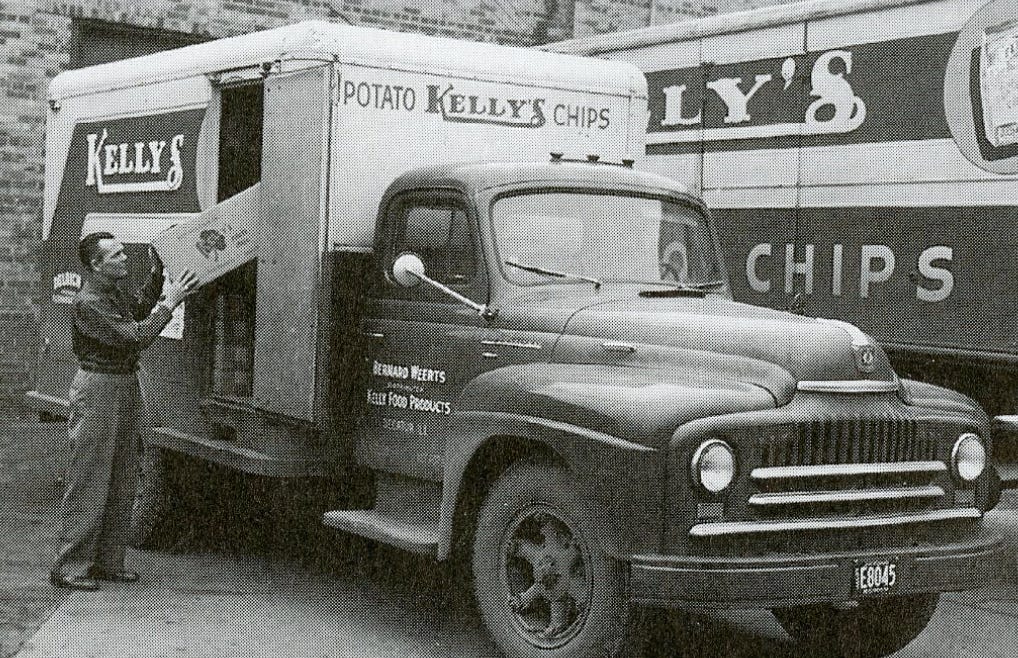

One fall day in 1982, my kindergarten class at Dennis Elementary School in Decatur, Illinois, took a field trip to the Kelly’s Potato Chip factory. It was magical. I can still smell the potatoes boiling in the fryers and taste the hot salty samples they passed out at the end. It bettered my disposition toward formal education. Up to that point, I’d been a skeptical participant. Finally, I thought to myself, after all this nonsense about the alphabet, all this waiting in line for half a sip at the drinking fountain, we’re getting to the real stuff. The snacks. How they are made.

It’s one of my few kindergarten memories.1 I’m getting old. I can’t tell you what songs we sang or what we did during rug time. But I won’t forget the potato chip factory.

I’m not alone. Ask anybody to name their best day at school and they are going to tell you about a field trip almost every time.

Friends, I have news: The venerable institution of field trips is in trouble. We need to save it — so it can revive our flagging schools.

A Brief History of Field Trips

Long before my turn as a processed food tourist, field trips were invented by progressive educators who believed children learn best from engagement with the real world. They called it nature study — a focus on tangible objects, not printed books. Prominent boosters included John Dewey.

But transporting classes of students long distances was infeasible. That’s why they became “field” trips. Most destinations were walkable and nearby. Teachers pointed out fish in streams or taught the names of trees in the forest. Students romped.

Modern field trips came about with the advent of better transportation. In 1927, a Georgia Ford dealer named A.L. Luce built the first modern school bus by bolting a wooden body onto a truck chassis. Voilà. A century later, his company is still among the nation’s largest manufacturers of buses.

The distinctive yellow color was standardized in 1939 to make black lettering easier to read. My Baltimore middle school students of the 1990s referred to such vehicles exclusively as “cheese buses.” They were cheap and simple. A cheese bus could get us to Philadelphia or D.C. and back the same day.2 The possibility of an on-board bathroom was absurd.

Roomy modes of conveyance and better roads turned many American museums from stuffy showplaces into educational institutions. After World War II, waves of little baby boomers consumed art and natural history in record numbers. Sputnik sparked a boom for new science centers that lasted until the Millennium.

OK, fine, you say. Millions of kids rode cheese buses to museums where they pretended to pay attention to tour guides. They ate room-temperature bagged lunches. They annoyed their chaperones. They pressed their bare butts up against the bus windows, to the horror of passing cars. They thanked the heavens for sparing them from class. But was there any real educational value to this time, expense, and fuss?

Yes, there was.

Evidence Says Field Trips Work

Researchers have discovered that field trips are more than a reprieve from school tedium.

Jay Greene and a group of colleagues found that students who visited an art museum showed stronger critical thinking and higher subsequent interest in learning about art than a control group. They achieved better scores on measures of “historical empathy” — the ability to understand and appreciate what life was like for people who lived in a different time - and tolerance of differing viewpoints. Given the challenges facing our schools today, that sounds like the perfect elixir.

Greene later found similar benefits for live theatre. I find this wholly believable. Have you ever read a Shakespearean play end-to-end? Boring and wordy. How about watching a filmed performance on TV? Stink-a-rino. But a live performance? Transformative. Kids are engrossed.

In 2020, Greene was part of another team that found students randomly selected for arts-based field trips had fewer behavioral infractions and attended school more often.

It’s not just the arts. Outdoor trips have been shown to boost critical thinking, perseverance, teamwork, and a connection to nature.

These aren’t graduation trips to Six Flags or afternoons at a bowling alley for making the honor roll. We’re talking about purposeful endeavors that are instructional, guided, and typically bookended with a real debrief. They aren’t a distraction from learning — they are learning.

There you have it: vindication for field trips. The juice is worth the squeeze.

Why Are Field Trips Dying?

Field trips entered a great period of decline in the early 2000s - well before research studies had shown their substantial benefits.

Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History once welcomed more than 300,000 students per year. By 2014, it was down to 200,000. Post-pandemic, it shrank even further, to 138,000.3

A 2023 study of nationally-recognized art museums concluded that 15 out of 18 had experienced field trip attendance losses since the early 2000s — typically 30-60 percent.

There are several common explanations:

Accountability ruined the fun. This is the factor most often cited by educators to researchers. The rise of standards and testing in the 1990s - followed by No Child Left Behind in 2001 - raised pressure on educators to deliver higher scores at all costs.4 No time for out-of-school junkets.

Field trips got privatized. As dollars were prioritized for raising achievement, Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs) often allayed district reluctance by offering to raise funds for field trips. You can guess how this went. More affluent kids kept visiting museums. Less affluent kids got double blocks of language arts and a video about pyramids.5

Principals hesitated to approve trips. They worried not just about costs and time but safety, logistics, and alignment to the school’s instructional needs. Some teachers simply stopped asking.

The Great Recession was brutal. Massive budget cuts after the 2008 financial crash put field trips on the chopping block. More than half of districts reported imposing limitations by 2010-11. Field trip attendance at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County dropped by 30 percent in just two years following the financial crash.

Buses became a pain. After COVID, the good old days of affordable cheese buses were gone. Driver shortages and fuel costs forced districts to prioritize getting students to and from school. Midday field trips were a primary casualty.

Save Field Trips, Conquer the Suck Factor

Potato chips notwithstanding, my purpose here is not nostalgia.

I’m concerned that the decline of field trips - which has lasted decades, persisting after serious accountability evaporated with the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015 and school budgets rebounded to new records in the wake of the recession - points to a larger loss of vibrancy in our schools. We see it in lower performance, higher chronic absenteeism, and epidemic loneliness.

The technical term for this phenomenon is the “suck factor.” School begins to absorb a general quality of sucking. Nobody wants it to suck, but it does. Everyone feels it.

We’ve known for over a decade that high-quality field trips invigorate kids in all the best ways - and they improve academic performance rather than dragging it down. And day after day, apparently, we do nothing with this information.

Instead, we are playing it safe, doing what’s easy and routine. The equivalent of a football team punting on 4th and 1 rather than playing to win. And the longer we acquiesce, the more the suck factor is growing.

Field trips can help us defeat the suck factor - if we commit to them.

Education leaders are fond of saying we need to make hard choices. I agree. They tell us money is tight and every penny must be spent wisely. I’m not arguing otherwise.

So let’s make a hard choice to ensure we can fund field trips that will open minds and lead to lasting memories. Where can we find the resources?

What if we stop spending so much on technology for elementary students?

Some of my readers just exploded with indignation. Curses have been muttered. I hear you — you are saying AI is the future, tech helps us personalize instruction, I need to see a demonstration of this new platform that’s transformative, I just haven’t seen it done right yet.

Maybe all that’s true, but I don’t find the evidence very persuasive. K-12 tech spending is now ~$30 billion per year. That’s something like $550 per student. Results have been lackluster. Yet we keep pouring more money into that hole and wondering where it went.

Are we sure, for instance, that we need 1:1 screen devices for kids in grades K-4? Most schools have had them for the past decade, which will go down as the worst stretch in the recorded history of U.S. schools when it comes to learning and engagement.

What we need is kids back on cheese buses.

My proposition: One serious field trip per year for kids through eighth grade. We’ll get them talking to each other, using their eyeballs to look at something besides screens, and recognizing that the world contains marvels.

The Kelly’s Potato Chip factory may be long gone, but its magic endures.

Here comes the fun part

Over the past month, I pestered school leaders, public officials, professors, journalists, random parents, and people I ran into at the airport with the same question:

What is a memorable field trip you took as a student?

These are their responses. They warm my heart. When you get to the end, please add your own in the comments if you have one!

“Alcatraz, 4th grade. Fun ferry ride to the island and then a cool guided tour. Just seeing the size of cells and picturing what solitary confinement would be like.”

“When I was in the sixth grade, we went to NASA space camp in Huntsville, AL. To experience floating inside a unit simulating space and return home to no inside plumbing was a stark dissonance and a demarcation line for me that I could - and would - have a very different life as an adult.”

“We went to a ‘pink’ pine forest in Allegheny state park and went for a long hike - as a kid it felt like miles and miles. I can still close my eyes and see the pink forest.”

“We took multiple trips to the Morris County Museum in elementary school. They had an amazing collection of geodes and rocks, and you could buy small samples in the gift shop. We collected them.”

“Trip to DC in 5th or 6th grade - first time there, seeing the sites I had only seen pictures of, the White House, Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, etc. Down and back in one day by bus, bag lunches from home, but a memorable and special day.”

“In 4th grade, we visited a hospital. We were shown the lung of a deceased person who smoked. And a lung of a non smoker. Suffice to say, I don’t smoke. Scared straight, the smoking edition.”

“I went with school to Yosemite—my first time in a national park, and my first time backpacking. It changed my life. I was a city kid who had never slept outside or seen stars. The trip did what school does at its best—it opened the world a bit wider.”

“An architectural tour of St. Louis, sometime in high school. Led by our history teacher, so it was only tangentially related to the subject. But I had no idea that St. Louis had so many beautiful old buildings.”

“A trip to Clove Lake Park on Staten Island, nice park, a picnic lunch, some relay races and general running around, but seemed like another world from our urban Brooklyn neighborhood.”

“My 8th grade year as part of graduation week, my class went to Dauphin Island Sea Lab— it made me want to be a marine biologist.”

“I remember a field trip to the Field Museum in Chicago -- we lived a couple hours away in Michigan -- and it felt both enormous and surreal. How could humanity have done all this, so long ago, and still have it sitting right next to where the Bears football team plays? Our teachers did a great job of making it fun. Plus a girl I thought was cute was in my group. So yeah, a good day all around.”

“AP History class trip to Williamsburg, UVA, and Monticello. Growing up in the Deep South and never travelling that far before, it finally dawned on me that all this stuff we studied in class was actually real because I saw the places where it happened. I fell in the James River because I wanted to touch the water.”

“My small town San Bernardino County high school was one of many Southern California school districts invited to participate in a Student for a Day event at UCLA, where among other things, we got to attend classes, eat in the dorms, talk with undergraduates and so on. The class I got assigned to was in the giant, ornate old Royce Hall where none other than Angela Davis was the professor. As she thundered forth from the podium, I was dumbstruck. If this is what college is, I thought to myself, I can’t wait.”

“The Wonderbread factory. I was a third grader in a public school in DC, and I haven’t a clue where our classic yellow bus took us. But it couldn’t have been too far. I still vividly remember the extraordinary aroma that permeated the air. I realize now that Wonderbread is to bread what Velveeta is to cheese. But the memory completely stuck.”

“Had the same science teacher for 7th/8th grade. She would take us to a nearby forest with a pond. Just looked it up on Google Maps, it was located in the back of my K-8 school. Fooled me, as it felt a world away, back then.

Over those two school years, we went to that forest/pond during all of Minnesota’s seasons. Likely the reason I was drawn to the sciences thereafter.”

“I loved the ones at interactive science centers like the LA Science Museum where you could make things, experiment with things, and see things like gravity and other conceptual science and math concepts in action.”

“The summer after 9th grade my earth science teacher organized a camping/hiking trip across the Southwest. We flew into Phoenix and rented a couple vans, hit places like Sedona, Four Corners, Grand Canyon, Yosemite. I grew up in a small town in Virginia. Camping under the stars at the Grand Canyon might as well have been exploring a whole other country.”

“Williamsburg, VA. It was the first time I had stayed in a hotel.”

“My school took us to Northern Minnesota for a sleepaway camp. The formal socialization (see: trust falls, obstacle courses) and informal socialization (see: middle schoolers bunking up together with no care for the lights out policy) sticks out for me as someone who was otherwise not really exposed to a lot outside of my immediate family.”

“In central Virginia, we took buses up to the Smithsonian almost every year in middle school. They would drop us off at the cast iron dinosaur sculptures outside the Natural History Museum and tell us to get back to the triceratops by whatever time in the afternoon we had to leave. What I remember is the freedom to roam wherever we wanted. It was oddly routine and glorious at the same time.”

Your turn - the comments are open.

I do remember my teacher. Huge shout to you, Mrs. Davis. I am sorry for being a pain.

Not all field trips require buses, of course. My favorite trips as an educator came when I was teaching in DREAM’s summer program circa 2000. Every Friday, we walked or took the subway to the best sites New York City had to offer - the American Museum of Natural History, the Cloisters … even a Mets game. It’s a coin toss as to whether the kids or the adults had more fun. (If you don’t know DREAM, do yourself a favor and check them out.)

Of those, just one-third were from Chicago Public Schools. Surely we can ensure more city kids experience the world-class institutions in their own backyard.

Some critics of testing and accountability were actually making this argument before NCLB passed. Here’s Alfie Kohn from August 2001.

Montgomery County, MD did a full-on investigation into this issue.

In middle school we went on a series of walking field trips around Cambridge where we studied the various monuments around the city and learned about their historical significance. I still remember leaning over my clipboard on the Cambridge Common, writing notes about Irish famine monument there. Later we designed and built a model of a monument of our own to something we deemed worthy of commemorating.

Both my kids were lucky to have a veteran teacher in their public preschool who was an intrepid field tripper. An annual favorite was always “take the subway <somewhere> and then come back.” 3 and 4 year olds can learn a lot about city life from a ride on MBTA with a great teacher!

I want to second the ideas in this post for several reasons:

1) The evidence by Jay Greene and his colleagues for the impact of well-designed visits to museums and theatre is VERY compelling. The museum study, for example, found an impact on critical thinking when students later were asked to evaluate a piece of art that they had not seen before. This is exactly the type of deeper learning, durable, and transportable skills envisioned in "portraits of a graduate."

2) In addition to the examples in this piece, there is also good experimental data (see research by Courtney Collins et al.) that shows positive impact (vocabulary, knowledge) of well-designed visits to zoos and aquariums as well. One interesting study also found a positive impact from well-designed zoo visits on reduction of negative behavior.

3) An analysis of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Surveys that shows disparities in visits to these types of institutions by socioeconomic status. This elevates the importance of school-based field trips. It gives some children the opportunity to have experiences through school that other children get through home.

4) Finally, museums, zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and historical sites are well-suited to help children with a particular class of skills -- unconstrained skills -- that are the bottleneck for improving reading and math achievement. These skills develop from direct and indirect instruction and experiences inside and outside of school. I wrote a post a few months ago about the importance of this type of informal learning experiences: https://www.unconstrainedkids.com/p/how-informal-learning-can-help-to